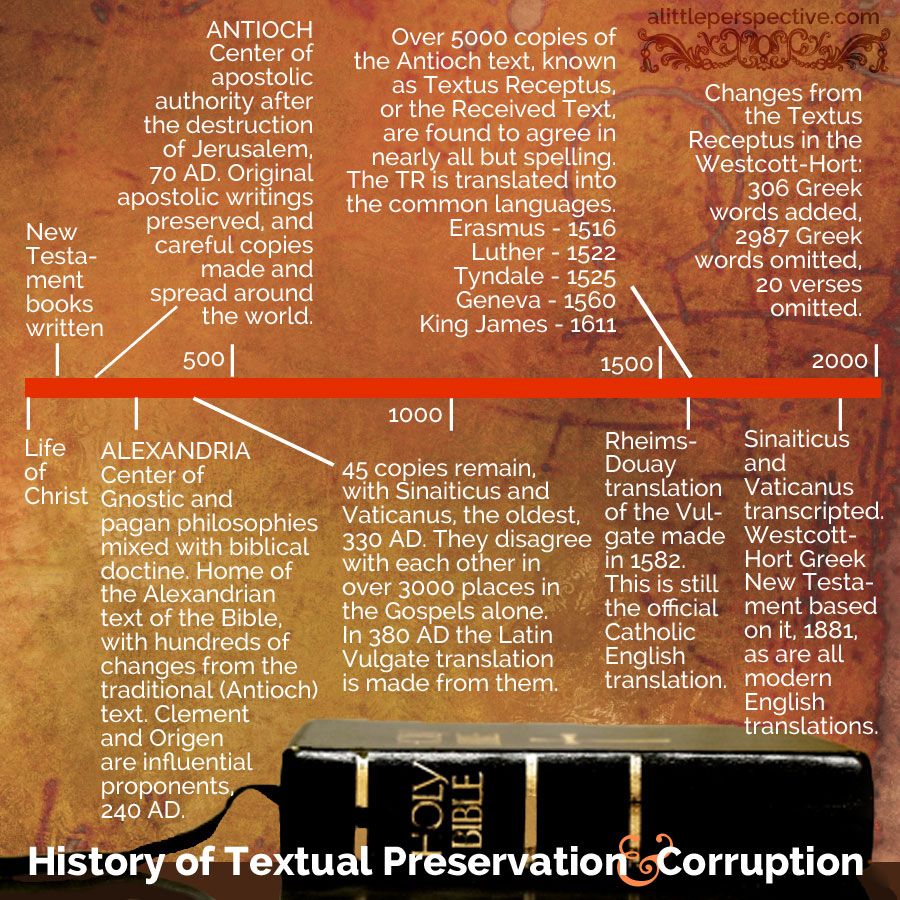

I have been rereading Dr. Floyd Nolen Jones’ excellent Which Version is the Bible? You can buy it from Amazon, but since Dr. Jones receives no remuneration from the sale of his books, go ahead and download it. He has made it freely available to all without cost, to help advance the cause of truth. In it, he traces the history of the preservation of the Biblical text, which the above chart illustrates.

But I ran across this bit of truth tucked into a footnote:

A typical “problem” or “unfortunate translation” offered against the KJB is found in Acts 12:4 where the Greek word “pascha” (πασχα) is rendered “Easter” instead of “Passover.” Although “Passover” is the usual correct rendering, the context of Acts 12:1–4 is unmistakable that it should not so be translated in this instance. Modern versions translate “pascha” as “Passover” here and in so doing rather than correcting a mistake, they actually insert one. As the King James is the only English translation available today that has made this proper distinction, this apparent error sets it clearly apart from and above all others (the 1534 William Tyndale, the 1557 Geneva Bible, the 1539 Great Bible – Cranmer’s – as well as other pre-King James English versions also read “Easter.”)

To explain, our computer reveals that the word “pascha” occurs 29 times in the New Testament. The KJB translators rendered it “Passover” the other 28 places in which it appears. The reader is reminded of the meticulous procedure to which the King James Bible was subjected and the large number of different scholars throughout England that viewed its production all along the way (see p. 66 ff.). The point that is being made is that these learned men clearly knew that pascha normally should mean “Passover” – for they so translated it the other 28 times. Therefore, Acts 12:4 is neither a mis-translation on their part nor an oversight! It is the result of a deliberate clear calculated decision on the part of many, many dedicated Christian scholars of the first rank. What did the 1611 translators (and their predecessors) perceive that led them to this obviously intentional choice which modern scholars have failed to observe? They were guided by the Holy Spirit to correctly discern the context and not merely blindly follow vocabulary and lexical studies.

The Passover was to be slain on the 14th of Nisan and the seven days following were the feast of unleavened bread (Nisan 15–21). Verse 3 informs us that Peter was arrested during the “days of unleavened bread.” Thus, the Passover had already come and gone. Herod (Agrippa) could not possibly have been referring to the Passover in this citation. The next Passover was a year away and the context of these verses does not permit that Herod intended to keep Peter incarcerated for so prolonged a period and then to put him to death a year later. No – it is clear that Herod purposed to slay Peter very soon thereafter.

The next key is that of Herod himself (12:1). Herod Agrippa was not a Jew. He was a pagan Idumaean (Edomite) appointed by Rome. He had no reason to keep the Jewish Passover. But there was a religious holy day that the whole world honored and does to this day – the ancient festival of Astarte, also known in other languages as Ishtar (pronounced “Easter.”) This festival has always been held late in the month of Nisan (c. April). Originally, it was a commemoration of the earth’s “regenerating” itself after the “death” of winter. It involved a celebration of reproduction and fertility; hence, the symbols of the festival were the rabbit and the egg – both well known for their reproductive abilities. The central figure of worship was the female deity and her child (see p. 98 ff.). The Scriptures refer to her as the “queen of heaven” (Jer.7:18; 44:15–27), the mother of Tammuz (Ezk.8:14), and Diana (or Artemis, Acts 19:23–41) and they declare that the pagan world worships her (Acts 19:27). These perverted rituals took place at sunrise on Easter morning (Ezk.8:13–16) whereas Passover was celebrated in the evening (Deu.16:6). Thus, the Jewish Passover was held in mid-Nisan and the pagan festival Easter was held later that same month.

As we have shown, Acts 12:4 cannot refer to Passover for the verse tells us that “then were the days of unleavened bread.” Thus, in context, it must be referring to another holy day (holiday) that is at hand, but after Passover. This suggests that Herod was a follower of that worldwide cult and thus had not slain Peter during the days of unleavened bread because he wanted to wait until Easter. As the Jews had put Jesus to death during Passover, Herod’s reason for delaying the execution certainly was not fear of their objection to such a desecration of their religious holy days. The King James translators realized that to render “pascha” as “Passover” in this instance was both impossible and erroneous. They correctly discerned that the word could include any religious holy day occurring in the month of Nisan. The choice of “Easter” was methodical, exact, and correct.

Dr. Floyd Nolen Jones

Which Version is the Bible?

Footnote 2, pg. 76.

UPDATE: I personally do not believe that “pascha” could mean any religious festival occurring in Nisan. Today in Jewish culture “Passover” is often used to indicate the entire week of Unleavened Bread interchangeably. However Luke was an exacting historian, and although he could have used “Passover” and “Unleavened Bread” interchangeably in Acts 12, it is a little unlike him to do so as Luke and the rest of Acts proclaim. But that Gentile translators in the 17th century wrestled with this translation thorn, and came to this conclusion, is a testament to the care which they took in their work. And how interesting to find the denunciation of Ishtar’s fertility festival in an unlooked-for place.

Leave a Reply